This week in Daak:

1. A Phoenix in her Ashes: Power, Politics and Desire in Parijat’s Poetry by Fiza Mishra

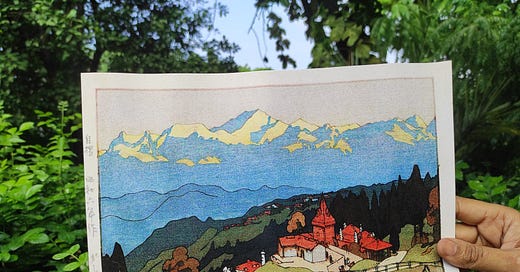

2. A Silent, Still Morning in Darjeeling

3. Daak Recommends

1. A Phoenix in her Ashes: Power, Politics and Desire in Parijat’s Poetry

Born in Darjeeling in 1937, Parijat spent her formative years safely tucked away from the tyranny of the Rana regime in Nepal, which created a political and cultural climate marked by a fearful silence. She lost her mother and elder brother very early on in her life, leaving her to the care of her father from whom she imbibed the philosophies of Marx, Engels and Gandhi. She joined the neo-Marxist Ralpha movement after migrating to Kathmandu as a teenager, allying with a group of musicians and writers in articulating the horrors of social injustice all across the Himalayan foothills through folk songs and popular culture. Most of her early years passed in this perennial state of transit, but tragically, a chronic illness which resulted in a partial paralysis, compelled the writer to spend the latter half of her life oscillating between a hospital bed in Delhi and her home in Nepal. This illness haunted her early works of poetry, infusing them with a deep cynicism and disillusionment with love, faith and humanity. One of her most famous (and favourite) poems, "A Sick Lover's Letter to Her Soldier" (Lahureldi Ek Rogi Premikako Palm), illustrates her profound despair with her own condition:

Life companion, much, much love;

I feel I might, send you a heart,

I feel I might send you a love letter,

tied round the necks of these free-flying pigeons,

repeating the sentiment of last century's love,

but what free bird could fly across today's lines and borders,

with what sighs could this withered existence lay down to rest in the winds of this world?

My love, I cannot raise you in my mind,

you are far away and hidden from me,

I cannot, speak to you, I cannot see you,

I do not even try to cross the seven seas to you,

and so I simply watch for you as I sit here all alone,

my brain as limited as my body,

Gautami turned to stone.

Love,

love is a mirage,

love is the greed of a goose,

love is a lifeless truth,

the thirst of a kakakul bird which loves the sun and blocks its setting;

an ephemeral body, an endless desire,

but love is the union of bodies,

me in your arms, each night,

a row of desires set out to block death — I am dreaming and burning my sweet dreams.

Beloved, you wrote to ask me

if I smiled in your billet picture,

you said you did not want to lose me,

you said my letter woke you up like a phoenix.

This is all just history now,

how I have survived I do not know,

I have waited long, you will surely come

to this phoenix in her ashes,

not rising to health once more.

(Translation by Michael Hutt, 1991)What did it mean for a mind so extraordinary to spend her life confined to a single room? Parijat found solace in cooking, gardening and inviting people over, populating her room with books, flowers and people who gathered there to exchange radical ideas. The faith she lacked in people and religion flowered, instead, in her belief in the power of literature, and the Marxist ideals she credited with saving her life. Her later writing seamlessly transitioned from her own unfulfillable yearnings to a renewed outcry against social atrocities. In “Memories of Mother on the Stone on the Gadhteer” (Gadhteerko Dhungama Aamako Samjhana), she illustrates the suffering of a Dalit woman wrenched away from her high-caste lover, and married off against her will.

I call the sun as my witness, the sky as my witness

Who does not fall in love in life?

…

The way the Mukhiya made the village shiver

How can I ever forget that, mother?

You the corpse-eating caste.

Marry away your daughter immediately

Or else, I will shave her head

Strip her off and parade naked around the village.

That’s how the Mukhiya had roared!

…

My mother! How am I to have one soul live in my heart

And spend life with another?

One visits me in my dreams

How am I to call the other by his name once I am awake?

(Translation by Mallika Shakya)Revered by writers across the world, Parijat created a body of work that transcended the notion of borders, crossing over frontiers as fiercely political as they were intimately personal.

By Fiza Mishra

Note: This essay primarily relied on the writings of Michael Hutt in Himalayan Voices: An Introduction to Modern Nepali Literature (1991), and Farhana Ibrahim in South Asian Borderlands: Mobility, History, Affect (2021).

2. A Silent, Still Morning in Darjeeling

3. Daak Recommends

Read another Daak on Parijat’s novel, The Blue Mimosa.

🫀