This week in Daak:

The second in this two-part series by our Reading Intern, Amun Chaudhary, continues the exploration of women’s literary contributions to the Urdu tradition.

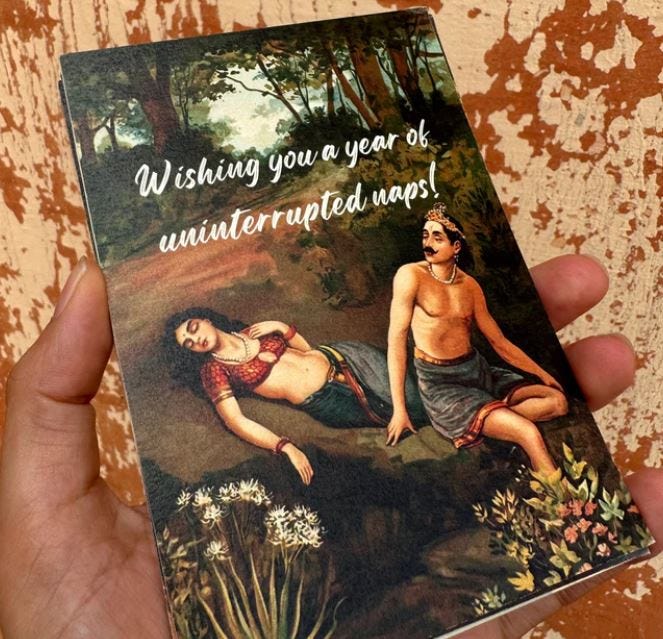

Also, check out our new postcards with a cheeky twist on classic artworks.

Finally, check out this week’s Daak Recommends for some rare delights!

1. Dangerous Women: Poets, Pariahs and Women Who Dared to Speak

Urdu poetry’s greatest marvel is its inherent ability to combine the political and the personal. One can read a sher and understand the deeply human experience of it, whilst also being clear on the political nature of that experience. Male poets who have done this in the past, famously Faiz and Iqbal, have been part of larger revolutions. However for women, the female experience in itself, and the choice to express it — that is the revolution. For this very reason, women in the Urdu tradition play a significant role.

Many pioneers of the Urdu literary tradition, such as the tawaifs who paved the way for the female voice, have been forgotten. Naturally, the Urdu ‘feminist’ canon built from this history has yet to be truly defined. Rukhsana Ahmed’s 1991 anthology, We Sinful Women, is arguably the first attempt at institutionalizing this genre in any form. The book includes poets Fahmida Riaz, Kishwar Naheed and other contemporary voices, but excludes household names like Parveen Shakir, generating an interesting debate about what makes up the Urdu feminist canon. It is important to note that the Urdu feminist canon in itself is a contradictory reality. Most women who form a part of it are either protected by their privilege or have dared to speak in ways that deem them dangerous to society, making them part of a subversion that goes beyond their writing.

As part of my reading internship, my goal has been to understand the Urdu feminist canon — who is a part of it, who gets excluded and what this qualification signifies. I have now realized these were the wrong questions to ask. Urdu feminist poetry refuses to fit within the establishments of literary tradition. This is partly because it was not born within these establishments, but mainly because the poetic expression of female experience is not one that needs to be institutionalized. It is the most authentic example of the relationship between the political and the personal. A woman’s choice to write poetry and center herself is, unbeknownst to her, a political choice. A woman’s choice to discuss the natural tenets of her life, her body, her desires, is a political choice.

One of the poets in Ahmed’s anthology is Sara Shagufta. Although she is now a well known poet, Shagufta’s life was filled with the sorrows of depression and loneliness and her poetry was merely an outlet for her mental health. She writes of her darkest thoughts, her biggest fears, and her sexuality. In the darkness of her poetic expression, Shagufta does not realize the societal envelope she is pushing. Without knowing it, Shagufta has produced a stark example of what it means to be an Urdu feminist poet, namely a woman who writes for herself, about herself, and most naturally, speaks for many other women. Below is a snippet from Shagufta’s poem Aurat aur Namak, (Woman and Salt):

عورت اور نمک

عزت کی بہت سی قسمیں ہیں

گھونگھٹ تھپڑ گندم

عزت کے تابوت میں قید کی میخیں ٹھونکی گئی ہیں

گھر سے لے کر فٹ پاتھ تک ہمارا نہیں

عزت ہمارے گزارے کی بات ہے

عزت کے نیزے سے ہمیں داغا جاتا ہے

عزت کی کنی ہماری زبان سے شروع ہوتی ہے

کوئی رات ہمارا نمک چکھ لے

تو ایک زندگی ہمیں بے ذائقہ روٹی کہا جاتا ہے

یہ کیسا بازار ہے

کہ رنگ ساز ہی پھیکا پڑا ہے

خلا کی ہتھیلی پہ پتنگیں مر رہی ہیں

There are many types of respectability

the veil, a slap, wheat,

Stakes of imprisonment are hammered into the coffin

of respectability

From house to pavement we own nothing

Respectability has to do with how we manage

respectability is the spear used to brand us

the selvedge of respectability begins on our tongues

If someone tastes the salt of our bodies at night

for a lifetime we become tasteless bread

Strange market this

where even the dyer has no colours

The kites on the palm of space are dyingOwing to her context, an Urdu feminist poet is, inherently and unfortunately, a pariah. So, when pariah and poet become synonymous, the literary canon becomes irrelevant and something more interesting is produced: a new understanding of change and revolution, and an acceptance that the legacy of women and Urdu literature will not be shaped by the same structures that produced male poets, or the poetic canon in general. Therefore, rather than spending time defining the Urdu feminist canon, to better understand our society’s ailments as well as its cures, it simply needs to be read.

By Amun Chaudhary

2. Some Cheeky Humour

We’re so excited to launch this new postcard set with a cheeky twist on classic artworks! Buy them individually or as a set of 10 to spread some smiles.

3. Daak Recommends

Watch this delightful recitation by Fahmida Riaz (another poet from the We Sinful Women anthology).

In the mood for some folk literature? Read some short stories from A. K. Ramanujan’s collection, A Flowering Tree and Other Oral Tales from India.

absolutely loved this piece!

I'll surely go and find more of these now :")