This week in Daak:

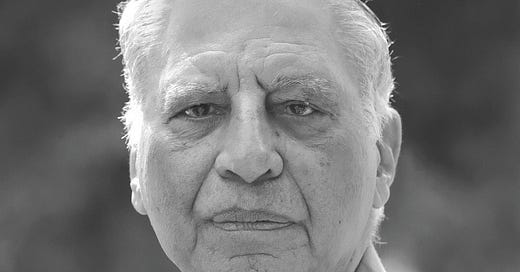

1. Death, Poetry and Memory: Remembering Keki Daruwalla

2. A Poem a Day

3. Daak Recommends

1. Death, Poetry and Memory: Remembering Keki Daruwalla

As the weather turns and trees begin to shed their leaves, we get a seasonal reminder of transience and mortality. Perhaps timed with this natural, unyielding rhythm — so indifferent to our finite ambitions and attachments — poet Keki Daruwalla has quietly breathed his last. Known for his kindness towards one and all, Daruwalla has left behind immense beauty in the form of his writings.

Born in 1937 in Lahore, Daruwalla moved to India during the Partition and later settled in Mumbai, where he completed his education and developed his literary career. In a parallel life, he served in the Indian Police Services (IPS) and later, in the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), a strange but synchronous exploration of the human experience.

An interviewer once asked him to describe his writing aesthetic to which he replied, “Koi aesthetic vesthetic nahin Madam. Jo dil mein aaya likh diya” (There’s no writing aesthetic, Madam. I wrote from the heart). Don’t be fooled by this simplistic remark; rife with evocative language and philosophical depth, his writing left a deep influence on English poetry in India.

From his rich oeuvre, we’ve picked a heartbreaking poem, “Nurse and Sentinel,” that speaks of duty, sacrifice, caretaking and death, but most importantly, of what keeps us alive, long after we’re gone. He asks, provocatively,

Why can't we define existence as something

that lives only in the awareness of others?

Do you exist if no one knows you do?

There can’t be a more fitting tribute to Daruwalla, who will continue to live on in the memory and awareness of the countless the people he touched with his words and deeds.

Read the full poem below.

Nurse and Sentinel

Reading poems on a hospital today

by a poet who attended on her grandmother,

I thought of you and your brittle-boned father.

Four months in a nursing home you stayed with him,

sleeping on a cane sofa, opening the windows

during half-charred nights, and taking in

the tarred air outside. You came home only for lunch

and cooked for him and took his food back, things he liked.

Once there wasn't any lunch for you—

you faced these blackouts rather well,

when people forgot you existed at all.

(Why can't we define existence as something

that lives only in the awareness of others?

Do you exist if no one knows you do?)

A thousand miles apart we talked on the phone—

the nights were bad, you said, but never mentioned

bedpans and things, cough and sputum.

How you trusted the imagination of others!

The bones healed, you made him walk.

But time is a disenchantress. Years later

he died, and you took care of the ceremonies.

I am always amazed that Parsee death rituals—

night-long nasal chanting,

sandalwood slivers

smuggled into the fire fringe,

priests scurrying around,

birds hanging in the air—

don't bring on other deaths.

Your mother thought well of all this and said,

you look after the dead very well.

And for once you answered back:

I looked after the living also, Mother.2. A Poem a Day

Want to start reading more poems from South Asia? Check out our poem-a-day calendar with poetry in different languages of the subcontinent. Best part? You can start using it anytime and it can be used year on year.

3. Daak Recommends

Read this touching, personal tribute to Daruwalla from an unlikely friend and read this interview (interspersed by poetry) with Daruwalla.

What a fitting tribute to the burden that caregivers bear.