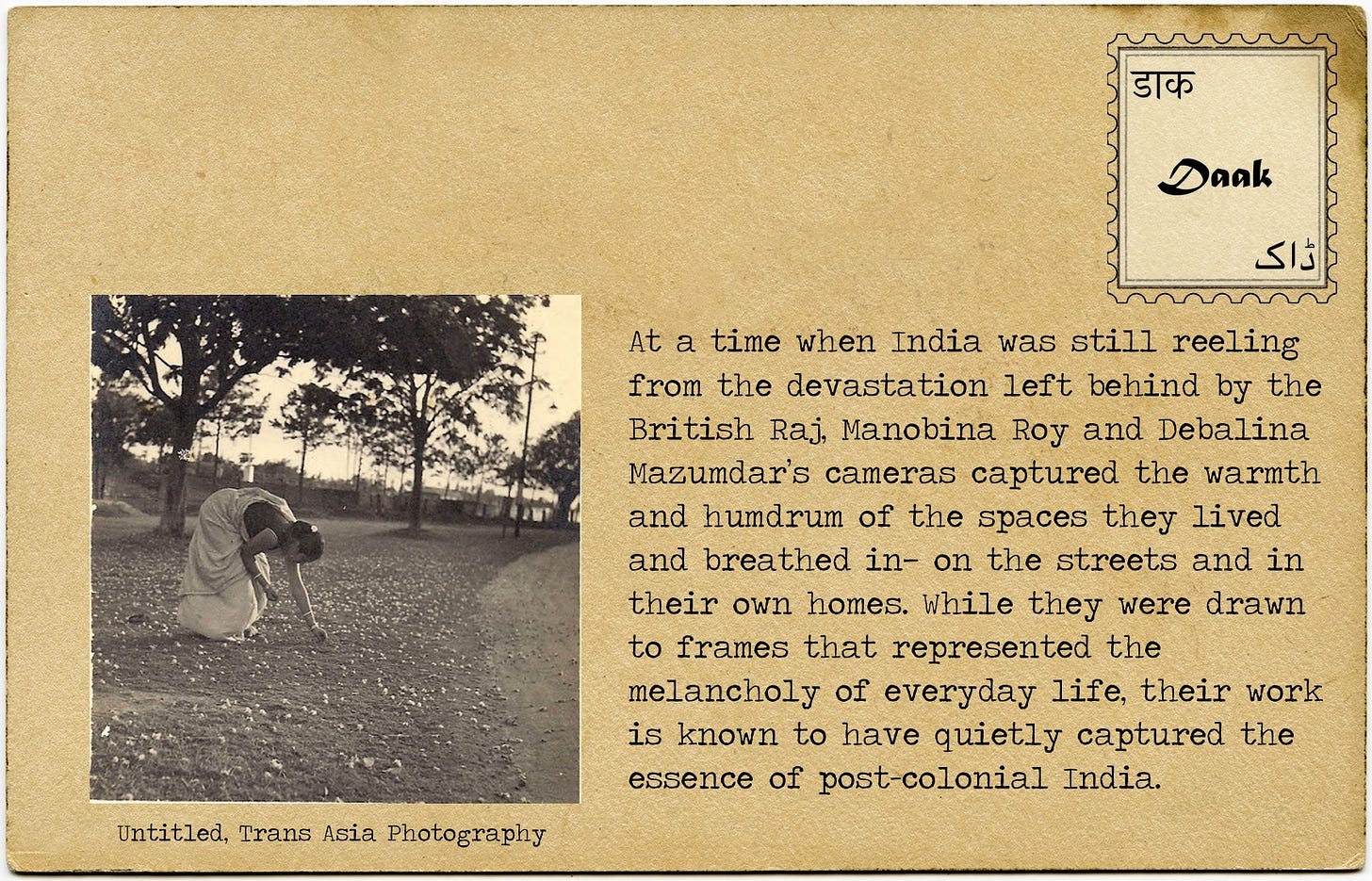

Of Memory and Melancholy: The Photography of Manobina Roy and Debalina Mazumdar

During the lockdown, we all became a little too familiar with the poignancy of photographs — when the whole world seemed to be crumbling around us, something as simple as a picture on a screen became a wistful memory of a time we desperately hoped to return to. Many artists and activists took seemingly mundane but hauntingly beautiful photographs of themselves in isolation, fascinated by the idea of finding love and intimacy in the act of being witnessed. This shared intimacy of photos became the hallmark of the images captured by the photographer duo of Manobina Roy and Debalina Mazumdar .

On a day in the early 20th century, deep within the nooks and crannies of an India hurtling towards independence, twin sisters Debalina and Manobina were given a Kodak Brownie camera by their father to celebrate their 12th birthday. His only condition was that they learn to process film and make prints— acts that they remained faithful to through their education and marriages, in spite of their husbands’ perfunctory support. The seductive play of light and shadow was an endless source of fascination for them — perhaps the reason for their love for black and white photography.

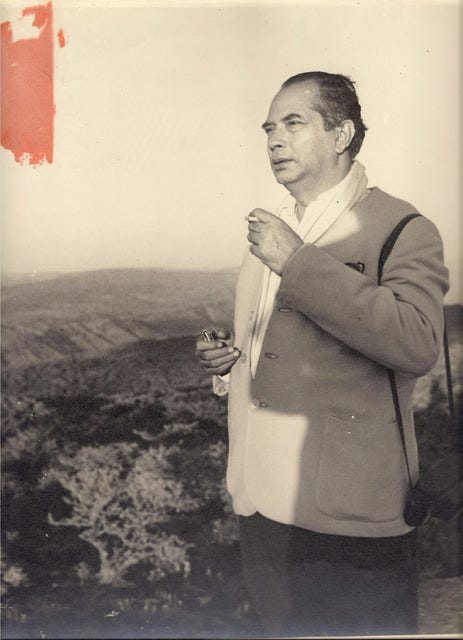

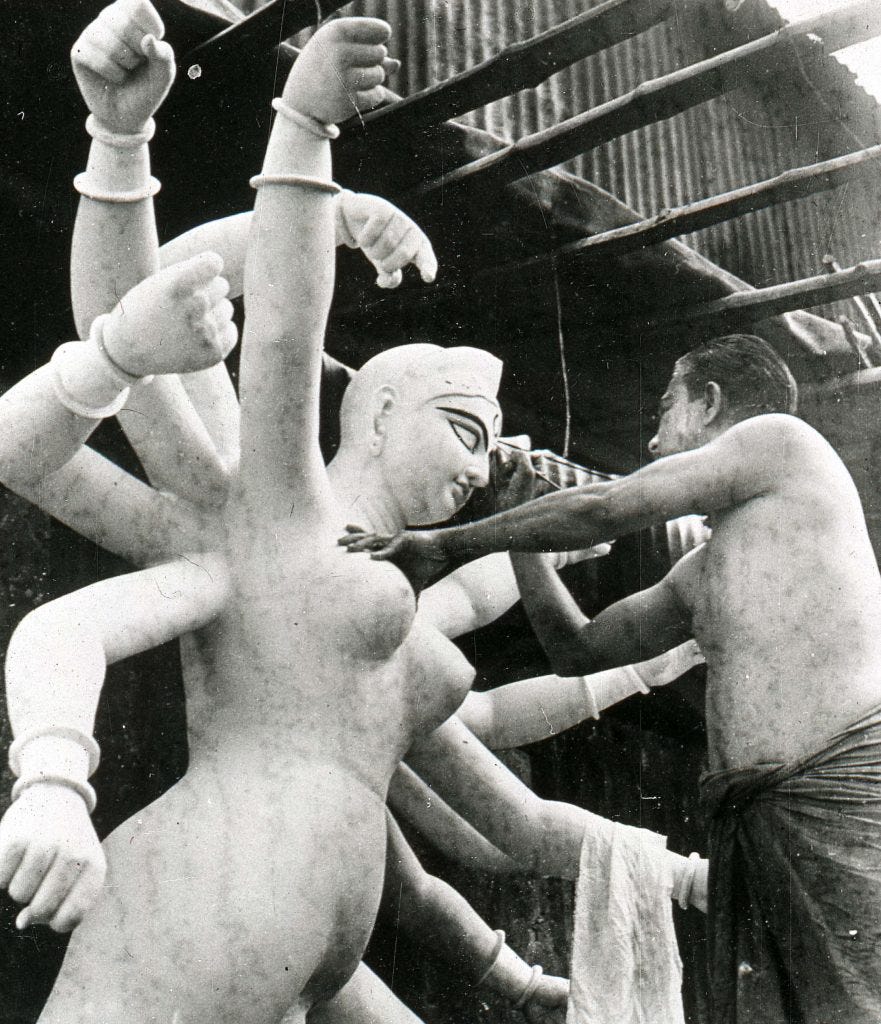

While photojournalists like Homai Vyarawalla were at the very centre of the political whirlwind, Debalina and Manobina captured the warmth and humdrum of the spaces they lived and breathed in — on the streets and in their own homes. A silver-fish eaten album which Debalina’s daughter Kamalani called “Sweet Memories, 1935” contains photographs of their father lighting a cigarette and writing at his desk, a cat basking in the sun, reflections of light filtering through the trees in a body of water— fondly credited to “LinaBina”, a combination of both their names.

Despite living in different parts of the country, they would often meet and travel the world together. With cameras hanging over their sarees and their children trailing behind them, they photographed strangers on the streets of London, Geneva and Moscow. Being the wife of the acclaimed filmmaker Bimal Roy, travelling gave Manobina the freedom she craved. After a trip to Moscow in 1959, she started writing a column for Femina on her travels and the pervasive racism and sexism in the industry. In an interview, Manobina once stated that their male colleagues went on to become respected faces in photography circles, while as amateur women photographers, the sisters were comparatively unrecognised. None of this, however, diminished their love for their art.

In an essay in the Indian Memory Project, Manobina’s son, Joy, recalls,

While my father was out working on films, my mother held the domestic fort, had four children, ensured we were all well cared for, and continued photographing, but mostly within the extended family – documenting our childhood, travels, events and family members. Known as the ‘lucky’ photographer, a matrimonial photograph of a girl taken by her would supposedly and immediately get marriage offers.

On hearing about Manobina’s domestic responsibilities, Devika Rani, one of the top stars of Indian cinema at the time, reportedly said “Now I know why Bimal Roy is so famous.” Unlike men in the creative space for whom undisturbed time to think has always been a birthright, the professional trajectories of women have almost always been shaped by demands of the home. “No one has ever done this for my photographs,” Manobina told her son during a photography exhibition of her husband's work, prompting him to build a retrospective titled “A Woman and her Camera”.

Both their work found a wide audience in magazines like the Illustrated Weekly of India. Even within their homes they were passionate archivists — each picture was carefully categorised, captioned and preserved. At the back of one such print, Manobina wrote,

Two old ladies meet on the road in London just to say ‘what a lovely day’ – they are so lonely – that just to be able to talk to someone – is a relief.

While they were drawn to frames that represented the melancholy of everyday life, Manobina Roy and Debalina Mazumdar’s work is known to have quietly captured the very essence of post-colonial India.

You can find more of their work here.

By Fiza Mishra