This week in Daak:

1. As we mark the beginning of Navratri, read an enlightening piece on Garba as a form of protest by one of our summer interns, Siddhi Vora

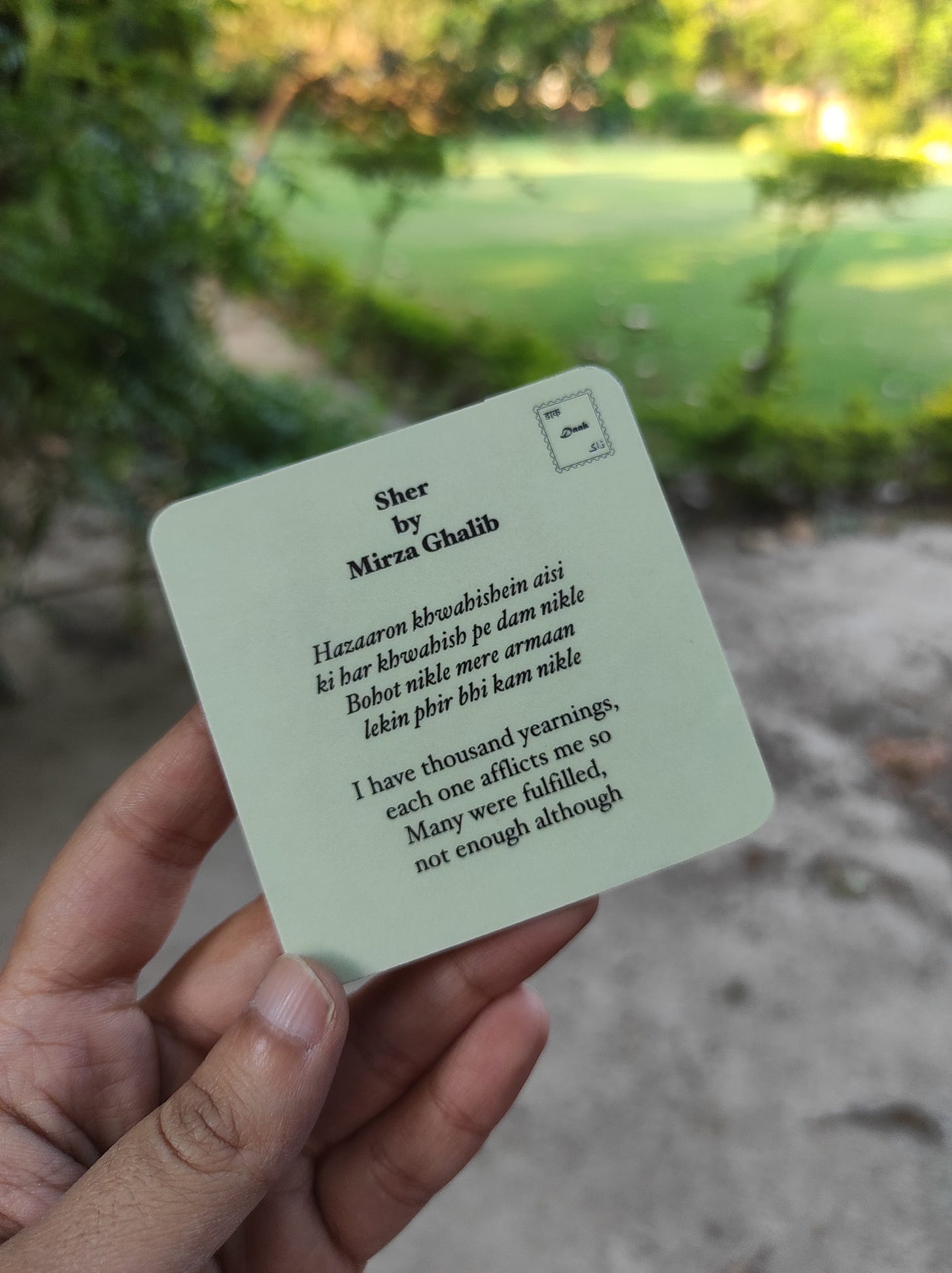

2. Poetry Belongs Everywhere

3. Daak Recommends

1. Poetic Resistance: Garba as a Form of Protest

Navratri is a larger than life celebration with nine incredible nights of high energy dancers prancing around each other in dynamic circles, twirling their chaniya cholis (traditional garba attire worn by women) and kediyos (worn by men) alike. At the center of this intricate performance is the steady beat of the garba song, which is essential to the whole enterprise. It guides the ebbs and flows of the garba circles and drives even the most tired of dancers into their third, fourth, fifth hour of dancing. It’s not difficult to imagine why or how generations have enjoyed garba folk songs. In fact, garba compositions remain an important oral tradition through which communities think through their problems and lives, and rearrange their social relationships.

Garba songs sung at Navratri dandiya-raas (socio-religious folk dance originating from Gujarat state in India) typically revolve around themes of Durga Ma, Krishna, or other religious icons. However, garba as a genre is much more expansive. Garba songs are folk songs, part of a long-standing oral tradition. The conventions of this genre — a simple and replicable melody, a driving beat and improvisable lyrics — lend garba folk songs the room for subversion. The beauty of these folk songs is that they offer a unique space for everyone to participate since there is no literacy barrier — as long as you can sing, you can be part of a new type of communal discussion.

Garba, as an oral tradition, bypasses the potential silence of written tradition. As a result, it can accommodate the perspectives of communities otherwise relegated to the side. Folk songs also hold two important characteristics: they provide anonymity, and they are set to catchy and memorable beats and melodies. Think of the folk songs that filled your childhood. Who wrote them? When? We may be able to name a few modern covers by famous singers but the identity of most of the original composers elude us. However, the melodies allow the message to be passed on for generations. This is profound, for folk songs then become a site of everyday protest. While they are indeed sites of socio-cultural discussions, garba folk songs are also sites of contestation and of struggle.

The Kutchi Mahila Vikas Sangathan’s community-led radio called Soorvani has gathered over 300 folk songs from the Kutch district in Gujarat. Here is one such folk song, set to a popular garba tune: a familiar toe-tapping rhythm accompanied by a pleasing warble singing out the words “sayaba, ekli hun vaitaru nahin karun.” The singer is calling out to her love that she will no longer tolerate an unequal share of labour and that she demands her share in property rights. “I will not slog alone any more, my love,” she says. “I want to be your equal, evermore, my love… I’ll be exploited no more, my love. Nor be the tolerant one, no not any more.” The full lyrics are as follows:

સાયબા એકલી હું વૈતરું નહી કરું

સાયબા મુને સરખાપણાની ઘણી હામ રે ઓ સાયબા

સાયબા એકલી હું વૈતરું નહી કરું

સાયબા તારી સાથે ખેતીનું કામ હું કરું

સાયબા જમીન તમારે નામે ઓ સાયબા

જમીન બધીજ તમારે નામે ઓ સાયબા

સાયબા એકલી હું વૈતરું નહી કરું

સાયબા મુને સરખાપણાની ઘણી હામ રે ઓ સાયબા

સાયબા એકલી હું વૈતરું નહી કરું

સાયબા હવે ઘરમાં ચૂપ નહી રહું

સાયબા હવે ઘરમાં ચૂપ નહી રહું

સાયબા જમીન કરાવું મારે નામે રે ઓ સાયબા

સાયબાહવે મિલકતમા લઈશ મારો ભાગ રે ઓ સાયબા

સાયબા હવે હું શોષણ હું નહી સહુ

સાયબા હવે હું શોષણ હું નહી સહુ

સાયબા મુને આગળ વધવાની ઘણી હામ રે ઓ સાયબા

સાયબા એકલી હું વૈતરું નહી કરું

સાયબા મુને સરખાપણાની ઘણી હામ રે ઓ સાયબા

સાયબા એકલી હું વૈતરું નહી કરું

I will not slog alone any more, my love

I want to be your equal, evermore, my love

I shall not slog alone any more

Like you I work on the fields

But the fields are all in your name

Oh the land bears your name, my love

I will not slog alone no more

I want to be your equal, evermore, my love

I will not slog alone any more.

I will not keep quiet at home any more

I will not hold my tongue, no more

I want my name in every acre

I will claim my share in the property papers

I want my share in the property papers, my love

I’ll be exploited no more, my love

Nor be the tolerant one, no not any more

I want to grow and do so much more

I will not slog alone any more

I want to be your equal, evermore, my love

I will not slog all alone any more.If folk songs are slices of history, then this garba composition tells a story of land ownership and livelihood discussions that have arisen in Gujarat in the past two decades. In “Family in Feminist Songs: A Continuity with Women’s Folk Literature,” Sonal Shukla writes that family might be the first patriarchal institution that socializes women and men and prepares them for their expected gender roles. While this is true, the folk songs our nanis, dadis, and baais sing still reveal undercurrents of protest. It may not be immediately apparent but the singers call into question family and gender norms. In “Sayaba, ekli hun vaitaru nahin karun,” the singer questions the legitimacy of established traditions and authority without completely dismissing them. In fact, she is questioning labor and family structures from within the structure itself. This composition is one such example of how women are not simply passive recipients of patriarchal institutions — they are active participants with agency.

Anthropologists Gloria Goodwin Raheja and Ann Grodzins Gold, in their book Reimagining Gender and Kinship in India, explore the poetics of resistance and the narrative forms women use to express their own experiences. In their final lines, they ponder the question “what is the use of songs and stories that tell of women’s power and agency when more authoritative and hegemonic voices threaten to drown them out?” But perhaps it is okay that such dissent simply exists. Such forms are not always or regularly successful in tearing down structures of hierarchy or dominance. However, as Raheja and Gold remind us, “the existence of subversive poetic genres remains an affront to any enterprise of domination or suppression.” Their existence reminds us that oppression is neither inevitable nor unquestionable.

By Siddhi Vora

2. Poetry Belongs Everywhere

Yes, even on your fridge! Get these poetry magnets and add beauty and inspiration to your space.

3. Daak Recommends

Curious about how the idols of Goddess Durga are made for the Puja celebrations? Check out this moving photo essay that captures the process and the stories of the people who toil for months to bring the Goddess to life!

Idol making must be work taking several months, given the huge demand for idols during the season. Yet from the photo essay it appears that working conditions of the artisans are harsh and facilities rudimentary. Are they paid decently at all? One would have thought that this holy business stretching over hundreds of years should have by now grown out of tin sheds and apparent exploitation of the workers?