The Diasporic Experience in Muna Madan: Laxmi Parsad Devkota’s Writing and Lain Singh Bangdel’s Painting

This week in Daak:

Thrilled to kick off a new series by our third Reading Intern, Sushan Bhattarai, who delved into Nepali Literature. In this week’s newsletter he covers Laxmi Parsad Devkota’s epic poem about love and loss, Muna Madan.

Also, explore our new line of tote bags with quirky Kalighat paintings.

Finally, check out this week’s Daak Recommends for some rare delights!

1. The Diasporic Experience in Muna Madan: Laxmi Parsad Devkota’s Writing and Lain Singh Bangdel’s Painting

Laxmi Prasad Devkota, according to one of his contemporaries—Bal Krishna Sama—was born thrice. Each birth was marked by Devkota’s dive into a new literary format, flawlessly switching from poetry and prose to short novels, testing and iterating on the vernacular like no one before him. Amongst his corpus, Devkota’s seminal work Muna Madan embodies his penchant for reality. At a time when Nepali was a medium for writing religious and heroic tales, Devkota held up a mirror to society, reflecting the truth of a common life.

In this episodic love poem, Madan goes to Lhasa in the hopes of finding better economic opportunities, leaving behind his beloved wife Muna and ailing mother in Kathmandu. He is momentarily hung up on his newfound riches, reneging on his promise of returning home, but ultimately realizes he must go back. However, by the time he gets to Kathmandu his home no longer exists. Muna dies love-stricken, tainted by false charges of adultery against Madan, and his mother due to old age. Unable to cope, Madan ultimately passes away too. Through this tragic tale, Devkota uncovers social prejudices and crafts poignant moments of reflection and realization for the protagonist.

Devkota’s radical approach is not limited to his substance. His poem is written in the asare jhayure, a poetic meter consisting of rhyming couplets, based on melodic rice-planting songs sung by Nepali farmers. Prior to this groundbreaking work, Nepali poetry had been largely confined to a select few, bounded by the constraints of classical Sanskrit meters, making it largely inaccessible to most lay people. Devkota’s poetry touched the masses due to its simple parlance, uncomplicated grammar, and recitable verse. In this endearing excerpt that is a culmination of Madan’s inner monologue after he is saved and nursed back to health by a Tibetan man, Devkota crafts a moment of realization where derogatory notions of caste are replaced by a moment of humanity.

ईश्वर मेरा हे भोटे दाइ ! क्या राम्रो वचन !

घरमा मेरी छन् बूढी आमा, ती सेतै फुलेकी,

घरमा मेरी जहान यौटी बत्ती झैँ बलेकी,

मलाई आज बचाइदैफ ईश्वरले हेर्नेछ,

मानिसलाई मढद्दृत गर्ने स्वर्गमा पर्नेछ,

क्षेत्रीको छोरो यो पाउ छुन्छ, घिनले छुँदैन;

मानिस ठूलो दिलले हुन्छ जातले हुँदैन !

O Bhote brother, my savior, how sweet

the words you speak! At home, I have an old mother

her head is white with age, I also have a wife

bright as a flame. Save me and God will look

after you. Those who help humankind

are blessed in Paradise. A Chhettri (Kshatriya)

born I touch these feet of yours with no disgust.

Man’s measure is his heart, not caste.Muna Madan is filled with vivid imagery that places the idea of home or Nepal in a rustic space outside of an urban center. The Nepali land is of particular interest to Devkota, and in his unusual opening dedication to the audience he evokes the Nepali soil.

नेपाली माटो स्वर्गको किरण रुरेर कन्क्यो मूल,

नेपाली बास्ना भएर निस्के अत्तर देशी फूल,

एकान्त वनमा फूलपरी रँगमा कस्सिए फुर्फुरी,

एक लहर टिपी चढाएँ, नाच् न् छातीमा हरघरी ।

Rays of heaven fell on the Nepali soil, all the roots vibrated and Nepali blooms

released their essence as fragrance.

In the secluded wilds, colorful flowers

danced wantonly. I offer you garlands,

let them dance forever upon your chest.Many in the Nepali diaspora can relate to Madan’s lamentations of home. This diasporic solidarity transcends time and space, and probably resonated with Lain Singh Bangdel, a 20th century polymath who not only pioneered the modern art movement in Nepal, but also pioneered repatriation stolen Nepali art.

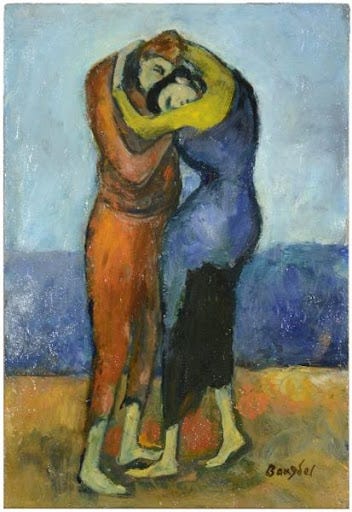

In 1936, Bangdel put Devkota’s work on the canvas, employing a confluence of local and international styles to depict a tender embrace between Muna and Madan. The sensuous fluidity of the figures as they lock together moments before departure transforms Devakota’s lyrical poem into a moving visual. The gentle treatment of the curves and the contrapposto position of the figures embody Nepali styles familiar in traditional art, like those found in bodhisattvas (enlightened Buddhist beings that guide others to nirvana). The bare feet of both characters are firmly planted on rusty demarcated ground, an ode to the importance of land. Madan’s fiery orange accentuates Muna’s darker blue, a contrast between love and duty.

Both Devkota and Bangdel portrayed the true lived experience of Nepalis. Devkota’s words challenged the elite literary establishment, locating the essence of Nepal in the country’s gritty lands, and the shackles of a middle-class promise. As a member of the diaspora whose family had moved to India for better opportunities, the story rang true for Bangdel, and in other paintings he would use abstracted mountains as a tether to his homeland. Although in a different format, Bangdel recognized and furthered Devkota’s work, embellishing it with the very best of 20th century artistic modernism.

By Sushan Bhattarai

2. New Line of Tote Bags with Quirky Kalighat Paintings

Carry your stuff in style with our new line of tote bags inspired by the fun, quirky and colourful Kalighat paintings which are guaranteed conversation starters!

3. Daak Recommends

Just like Madan in Devkota’s poem, male migration has been a common theme in the subcontinent. Read this interesting article about how this phenomenon, along with the introduction of trains, led to a special genre of Bhojpuri folk songs.

Speaking of folk music, listen to this lovely rendition of Bob Dylan’s Tambourine Man by Purna Das Baul, who belongs to the Baul community, an ancient group of wandering minstrels from Bengal.