The Tragedy of Rural Indian Life: Kamala Markandeya’s Novel, Nectar in a Sieve

Kamala Purnaiya Taylor, better known by her pseudonym, Kamala Markandeya (1924 - 2004), was born in a village near Mysore in India. She wrote ten novels, all of which dealt with postcolonial themes and traditional social systems in India. Written in English, the 1954 novel Nectar in a Sieve is her most famous work. It is the story of a woman, Rukmani, in her own voice.

The tale begins with Rukmani, a village girl, who is married off to a tenant farmer, and then traces the story of her life and family. While it is essentially a rural woman’s fictional autobiography, the narrative of the book boldly brings to light anxieties of post-independence India that was rapidly urbanizing, but also reeling under the effects of feudalism. Throughout the book, the reader experiences tragedy and poverty up close. You feel the haplessness of the narrator and her resignation to a life without luck because of a fault in her stars and the superstitions that surround her.

Rukmani’s life is uprooted and she moves from a relatively comfortable life as a headman’s daughter to her farmer husband’s humble home. In the years after, she witnesses modernity take over her village in the garb of a tannery which changes the dynamics of the town. Her life increasingly revolves around crop cycles, the bounty and misery of her life depending on the vagaries of nature. She faces death, starvation, moral dilemmas—treading the boundaries of what is expected of her as a good wife—and moves to a big city, eventually becoming a part of the vicious alms circle around temples.

There isn’t one great tragedy in the book as much as a fatalistic embrace of mishaps and misery. This is an intimate account of desperation up close. There is a little vulnerability and baring of the soul but mostly, it reads as an account of a life in which poverty is normal, even expected, and hunger the norm. The dialogues often make this evident. An instance of a sister crying at her brother’s death is met by this remark from the mother:

What are you crying for?’ I said. ‘ You have little enough strength, without dissolving it in tears.’

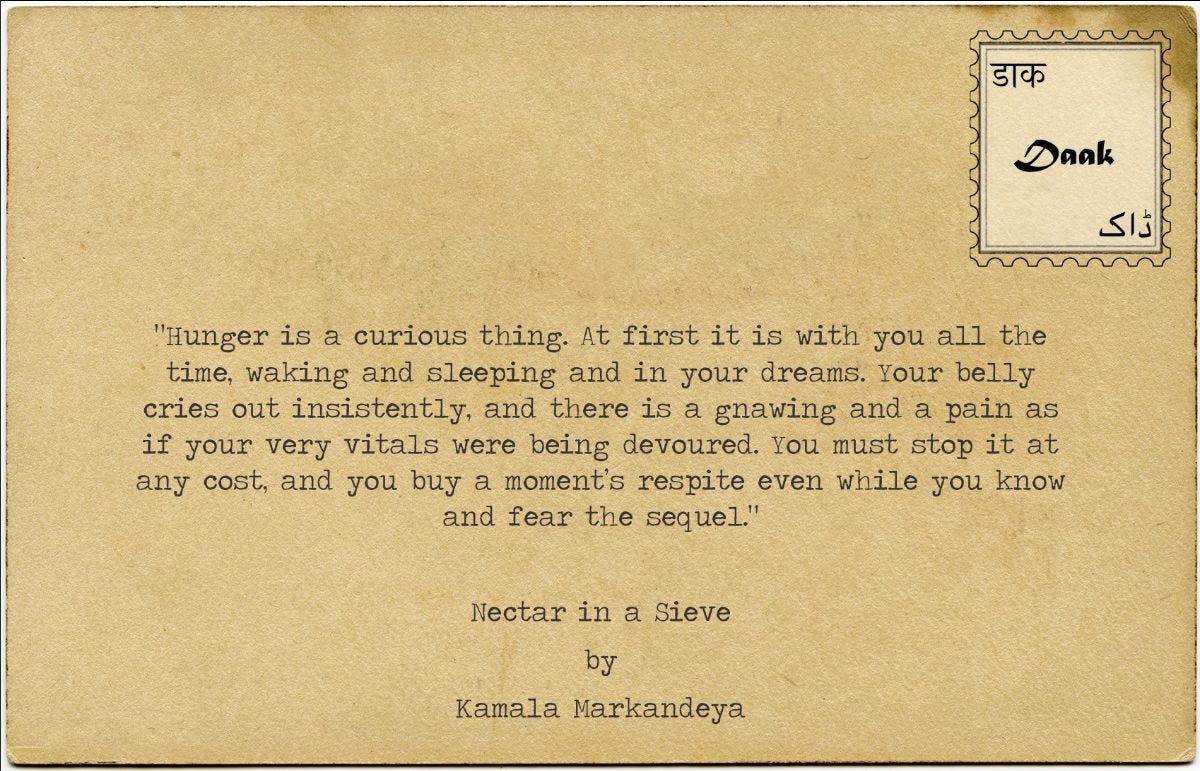

Markandeya’s prose is traditional, and at times a bit stiff, but always evocative. This passage describing hunger is one of the most moving passages in the book:

Hunger is a curious thing. At first it is with you all the time, waking and sleeping and in your dreams. Your belly cries out insistently, and there is a gnawing and a pain as if your very vitals were being devoured. You must stop it at any cost, and you buy a moment’s respite even while you know and fear the sequel.

Then the pain is no longer sharp but dull. This, too, is with you always, so that you think of food many times a day and each time a terrible sickness assails you, and because you know this you try to avoid the thought, but you cannot, it is with you.

Then that, too, is gone. All pain, all desire, only a great emptiness, like the sky, like a well in drought, and it is now that the strength drains from your limbs, and you try to rise and find you cannot, or to swallow water and your throat is powerless. Both the swallow and the effort of retaining the liquid tax you to the uttermost.

Throughout the novel, she introduces elements of class and the elite are often described as divorced from the lives of farmers. Their cold distance is evident in one passage where, blamed for a death in their factory, the manager offers a rather horrific consolation while trying to avoid compensating the family for it.

The point is, the other said, and he thumped on the floor to emphasize his point, ‘that no fault attaches to us. Absolutely none. Of course, as my friend has said, it is your loss. But not, remember, our responsibility. Perhaps,’ he went on, ‘ you may even be the better off… You have many mouths to feed, and – ‘

The thinner man raised his hand to check him, appalled by the words, yet scared by his own daring.